Safe Space

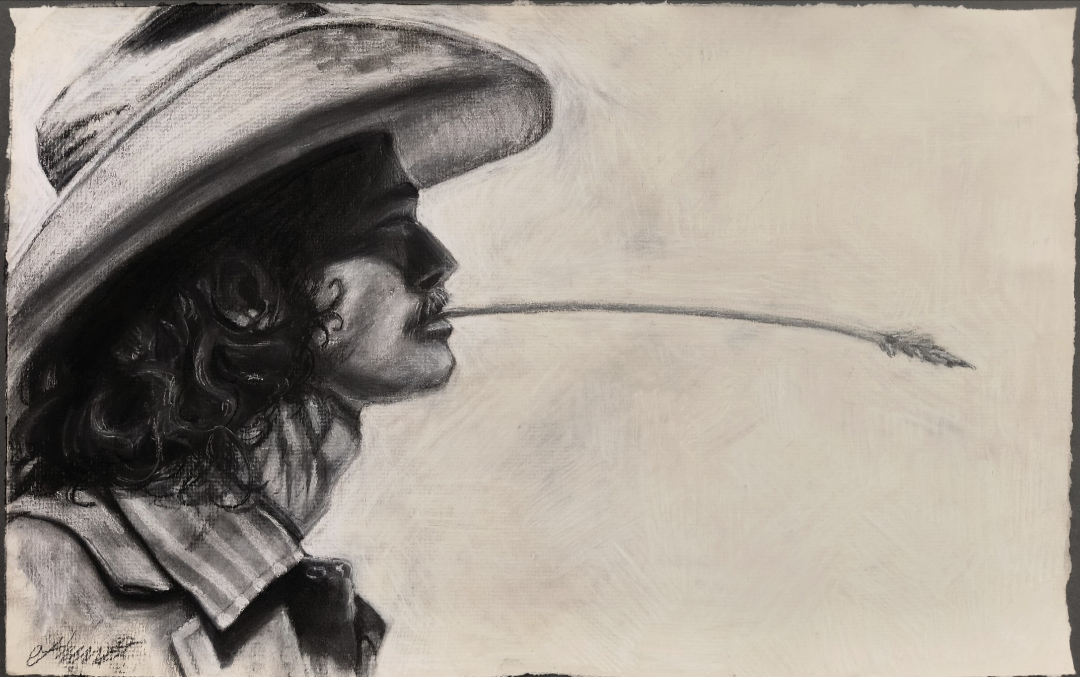

The Sunday before the planned protest, parents chalked the student parking lot with pride flags.

Dr. Moen reeled as she checked her inbox. Her mind raced, her heart pounded.

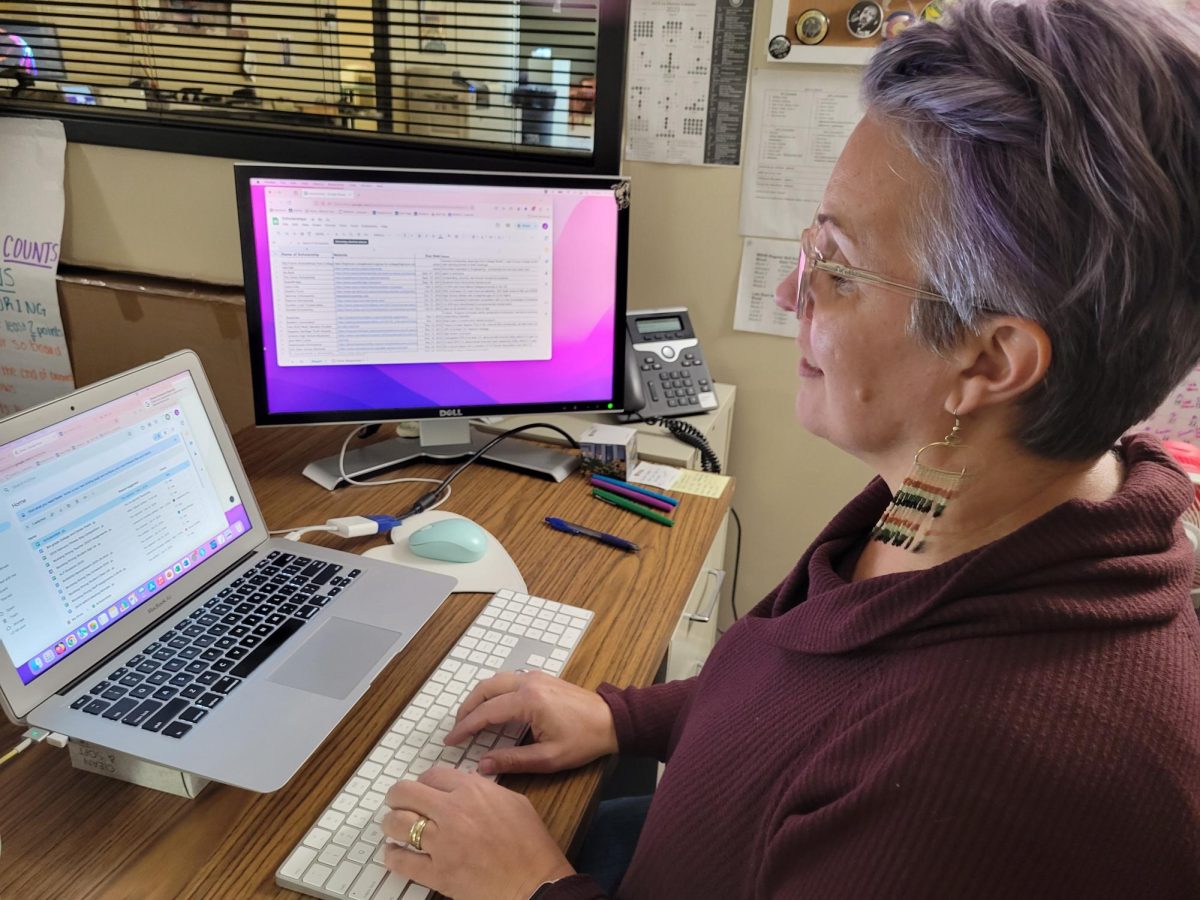

The email had seemed insignificant at first, just a note from another Manitou community member as Dr. Moen sat at her desk in the soft glow of her classroom, but then she opened the email to a screenshot of the Westboro Baptist Church protest schedule.

They’re coming to Manitou.

And it wasn’t just the town of Manitou they were coming to, but this radical hate group was coming right up to the high school: the high school where Dr. Moen taught her unique, wonderful students who would be targeted by these people. Ethically, Dr. Moen raged – this was horribly wrong – but personally she raged with even hotter fire. How would this hurt her GSTA kids? Dr. Moen’s own child was nonbinary – how would this hurt Rowan?

She felt her fists clench as she stared at her laptop. This was supposed to be a safe space. Kids came to school to learn, to grow, to be supported, not to be bullied by sanctimonious hypocrites and their “God hates fags” signs. The district couldn’t possibly let this happen. Something had to be done.

Dr. Domangue was driving home from a conference when her phone started ringing, and she glanced quickly away from the road to check the caller ID. It was from Suzi Thompson, the school district’s chief financial officer. She swiped up to accept the call and held the phone to her ear with her shoulder as she continued to drive.

“Hello?” Dr. Domangue answered.

“Hi, Elizabeth, it’s Suzi,” said Ms. Thompson. “We have a… situation.” “What’s going on?”

“Have you heard of Westboro Baptist Church?”

Dr. Domangue’s stomach dropped.

“They’re coming to protest at the high school on the 11th,” Ms. Thompson said.

Dr. Domangue clutched tightly at the steering wheel and focused hard not to swerve. “I

see.”

Why Manitou specifically? Why would they come to her school to harass her students?

What would she do? What would her students do? Would they be okay? Radical hate was no trifling matter.

“We’ll figure it out,” Dr. Domangue told Ms. Thompson over the phone, still white-knuckling the steering wheel. “We’ll handle it and we’ll keep our students safe.” She was trying to convince herself as much as anyone.

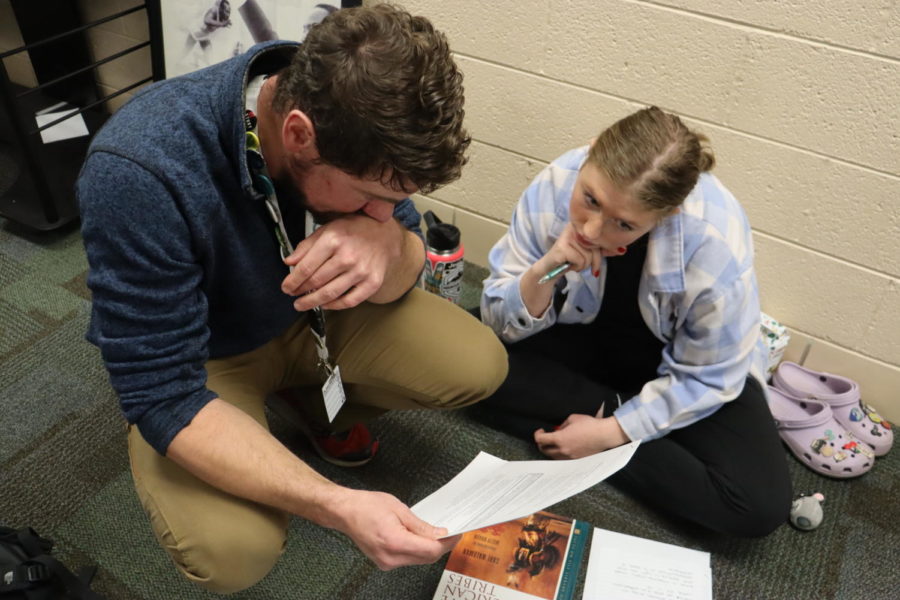

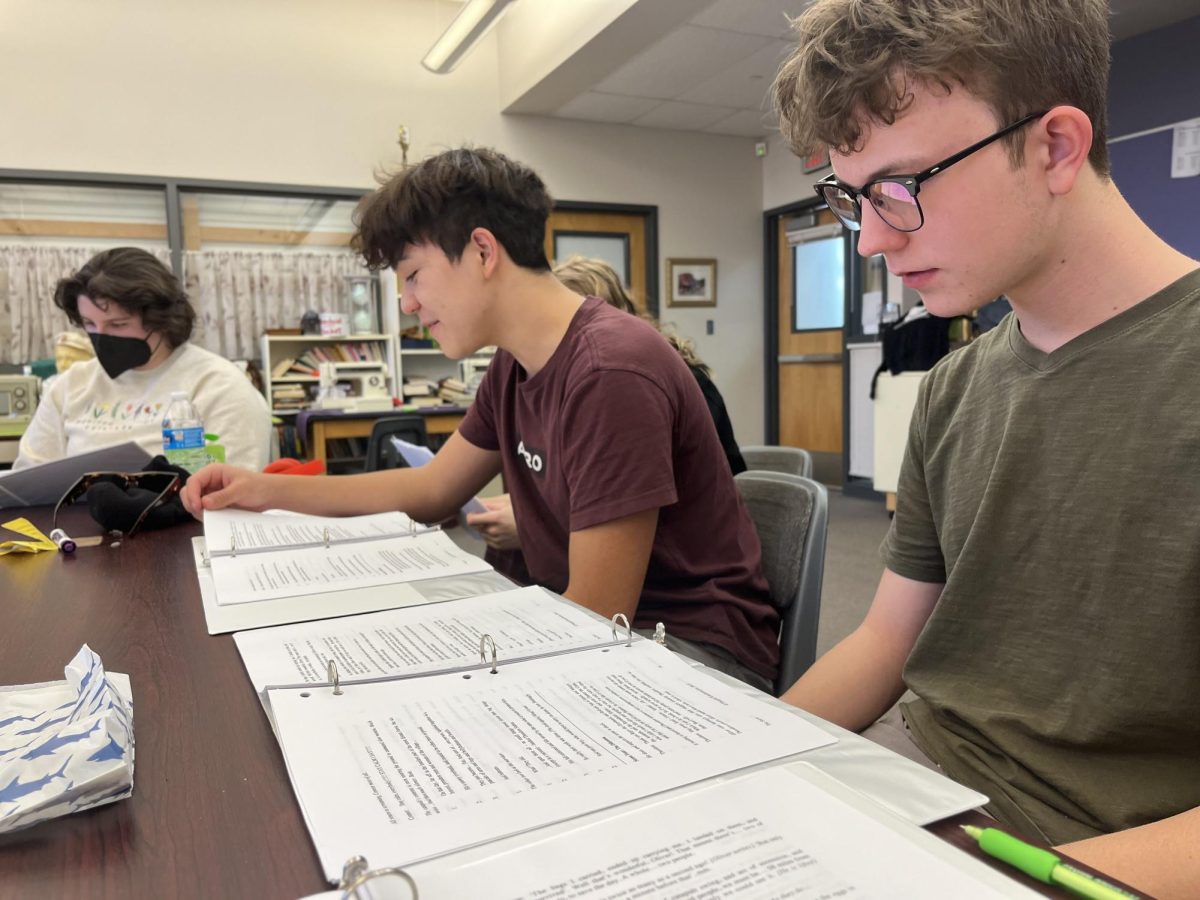

Mrs. Kerrigan marched down the hallway to Mr. Moeder-Chandler’s office. The click of her shoes on the tile floor of the high school hallway echoed dully against the battered green lockers. A list of scribbled ideas from NHS and GSTA, both clubs she advised, crumpled slightly in her fist.

She couldn’t believe this was still happening. When she was in college at the University of Kansas, Mrs. Kerrigan had only been a forty-five minute drive from Westboro Baptist Church. They had protested there often, even to Desmond Tutu when he had come to speak at her school. Who protested Desmond Tutu?

It was infuriating, then, to find that after all those years Westboro Baptist Church was still going at it, and not only that, but they were coming to Manitou. To the high school where Mrs. Kerrigan’s students were supposed to feel safe.

“We can’t just let them do this,” Mrs. Kerrigan told Mr. Moeder-Chandler. “We have to do something.”

She was sick of administration shooting things down because they were afraid of the responsibility that might come with action. They wouldn’t let NHS call the tailgate “tailgate against hate” and they wouldn’t let Mrs. Kerrigan’s journalism students write an article about the protest – against student press freedom, she might add. In admin’s attempt to stay positive and uplifting, they were completely glossing over the fact that students were experiencing hate.

Trying to channel her anger into something constructive, Mrs. Kerrigan threw out ideas her students had come up with and, after some back and forth with Mr. Moeder-Chandler, they had a plan set. In support of Manitou’s students, especially those who felt targeted by the protest, several groups would decorate the high school hallways with colorful posters and loving messages.

And they did. Manitou’s hallways became rainbows of support and positivity with posters from NHS, student council, GSTA, and even GSTA clubs from other schools in the area. The day before the protest, the school parking lot teemed with parents, staff, and Manitou community members drawing beautiful chalk pictures on the sidewalks and painting the crosswalk in a bright rainbow.

It buoyed Mrs. Kerrigan’s heart to watch them all laughing and smiling as they chalked rainbows and flowers. Manitou would make it through this.

At 4:00 in the morning on Monday, October 14, 2019, Dr. Domangue pulled up to the high school to join the protest response team. The sun had not yet risen, it was freezing cold, and

she was exhausted, both from the early morning and the stress of managing this whole crisis, but her adrenaline and determination to keep her school safe kept her going.

She waited diligently with the police department until people started arriving. The protestors weren’t legally allowed to step onto the school grounds, but they stood on one side of Manitou’s steep hill, flaunting their horrible signs. There were only six or seven of the protestors standing there, but their hostility was palpable.

Seeing the atrocious things on their signs, Dr. Domangue’s jaw clenched and she found herself glad she had called a two hour delay for the school. Students would have had to walk to school past these people and Dr. Domangue wanted to protect them from sick parts of the world like this as much as she could. The two hour delay call had been difficult to make – she wished they didn’t have to disturb Manitou’s regular schedule for these hypocritical fools – but it was for the safety of everyone involved.

Across from the protestors on the other side of the hill, the street filled with counter protestors. Dr. Domangue kept an eye on them, knowing situations like this could become violent, but it never did. It was just a community standing up for their students, honking and shouting to drown out unwanted hatred.

The stand-off continued through the morning until, in the frigid morning air, everything seemed to freeze.

Bounding up the street with noble strides came a deer. One leap after another, it passed everyone standing there and stopped at the crest of the hill in the space between groups. Silence settled and everyone stared at it. It stared back.

Moments passed without so much as a whisper of sound and the deer focused on the protestors with deep brown eyes. The only movement in the entire scene was the deer’s occasional flick of the ear.

Dr. Domangue held her breath and, like the morning’s own miracle, the protestors lowered their signs and disappeared down the side of the hill.

The response team and counter protestors stood in reflective shock, just watching the spot where the protestors had been standing only moments ago, and the deer ambled off the side of the hill to munch the overgrown grass.

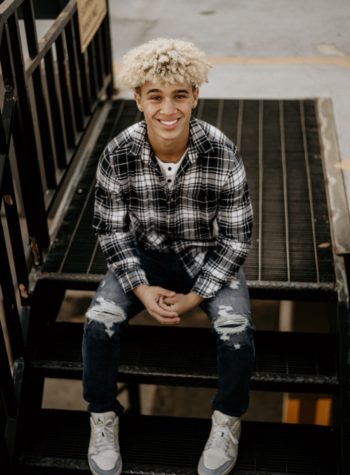

Two hours later, students began to arrive at school to a wholesome welcome. As students rounded the parking lot corner, they were greeted by the parking lot decorated from the day before and an enthusiastic group in front of the SILC building with flags supporting every group imaginable. There were pride flags, military flags, first responder flags, all waving in the gentle breeze of a morning overcome.

Students had nothing to fear with this immense support system behind them. Their parents, their teachers, their town community: they had all come together to engulf Manitou in positivity. Hatred may have tried to find its way to Manitou, but the strength of the community’s love proved unfaltering and impenetrable.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Manitou Springs High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and attend local conferences and trainings!