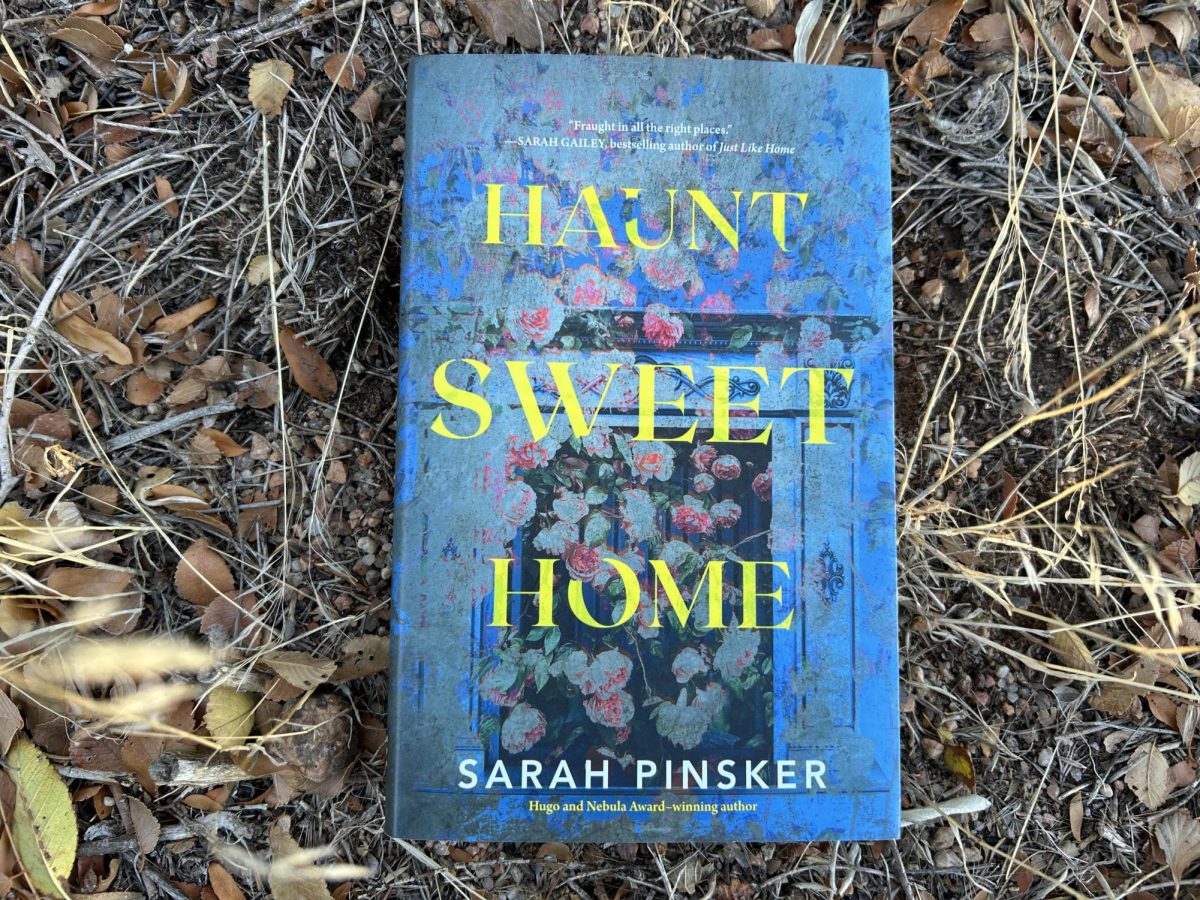

As a genre, historical fiction is almost exclusively Euro-centric, and novels that don’t deal with European history tend to chronicle the lives of the same handful of African or Asian characters, over and over again. Equal of the Sun, a novel by Anita Amirrezvani that deals with court life in 16th century Iran, was an unexpected and much-needed discovery at my local library. I loved this opportunity to look into a less widely explored culture, and the author’s focus on gender roles added even more to the overall experience.

Equal of the Sun is narrated by Javaher, a eunuch in the service of the shah who, over time, came into the service of Princess Pari. Pari was a powerful presence inside the royal harem and outside of it, and, in spite of her sex, managed to win more supporters and gain more credibility than many of the empire’s most powerful men. Initially, it is revealed that Javaher is writing this account of Pari’s life because no one else will do it—for some reason that goes unexplained, even mentioning her name puts his life in danger.

“My presence at court was ordained so that I could tell the true story of Pari Khan Khanoom, the lieutenant of my life, the khan of angels, the equal of the sun” (pg. 424).

Indeed, the relationship between Javaher and Princess Pari was one of the strongest cases of platonic love I’ve ever read. Javaher first enters Pari’s service at the recommendation of her father, the shah. Over the course of a few years, their bond grows beyond that of master and servant, as both come to trust each other and value the other’s opinion.

Even more significant in the relationship between Javaher and Pari is their role in life, this impression that they’ve transcended traditional gender roles to become, as Javaher puts it, a third sex. Both Pari and Javaher have devoted their lives to the service of the kingdom, putting their own personal lives and any other interests second that that goal.

“Our eyes locked in understanding. How different we were from ordinary men and women! No children would issue from our loins, but we would endure the birth pangs of a better Iran” (pg. 247).

Even more interesting and well-done than that, however, was the way Amirrezzvani examined and explored the mores and traditions of Iran in the middle ages, and discussed the way Princess Pari was able to thwart them. Though Pari’s close relatives respect and admire her, many of the different factions opposed the way she controlled and manipulated the shah to do her bidding. They were afraid of her power and resented the influence she wielded—obviously, nothing is more threatening to a man than a woman who knows how to use her brain, am I right?

From the outset of the novel to the very end, Pari’s attempts to create a better and grander Iran were thwarted by those who, technically speaking, were on the same side. On one occasion, one of her enemies composed a poem meant to keep Pari silent.

“Since women don’t have any brains, sense, or faith

Following them drags you down to a primitive state.

Women are good for nothing but making sons

Ignore them; seek truth from the light of brighter ones” (page 78).

Of course, Pari quickly responded with a poem of her own, deriding foolish and pretentious old men too blind to see the truth, and for that I really had to applaud her. Throughout Equal of the Sun, Princess Pari was portrayed as not only a strong-minded and determined woman, but as a role model to any woman who reads this book. Pari was certainly not perfect—our narrator Javaher is the first to admit to the princess’s faults—but no one is perfect, and I found that the sum total of Pari’s strengths and weaknesses led to create a realistic and admirable woman who most assuredly deserves readers’ respect.

And beyond Pari’s own struggles to stay in power, Amirrezvani also managed to insert some thoughtful and interesting comments on sexual objectification and gender roles in general (all couched as being the secret musings of Javaher the eunuch, of course).

“As [her laugh] faded I wondered, if boys and girls were so similar as love objects, both in paintings and in poetry, why were they treated so differently when they grew into men and women? What was the difference between having a tool and not having one? Even I could not say” (pg. 293).

Overarching ideas and themes aside, I’ll move on to technical aspects. Amirrezvani is a very, very good writer, and I was quite impressed with both her prose and the way she approached telling Princess Pari’s story—through the eyes of an objective observer. Pari’s character was only made stronger because of that. In terms of plot, Equal of the Sun is a book that deals with political intrigue, secrets, espionage, and more than one military coup. Readers who enjoy political-themed novels will be more than satisfied with this book.

Altogether, I very much enjoyed Equal of the Sun. Not only does this novel tell the story of a little-known historical figure, but Anita Amirrezvani does it in a way that shows the power of women in a time when men were heavily dominant (Princess Pari was a contemporary of Elizabeth I). I’m extremely, extremely impressed with this novel, and I think this author has a brilliant talent for storytelling and characterization. For those who enjoy historical fiction, strong female leads, or intelligent commentary on gender roles, this is a highly recommended read.

By Renae Musekamp

This book review was originally published at Respiring Thoughts on Feb. 15, 2013.