COVID-19 effects on student musicians

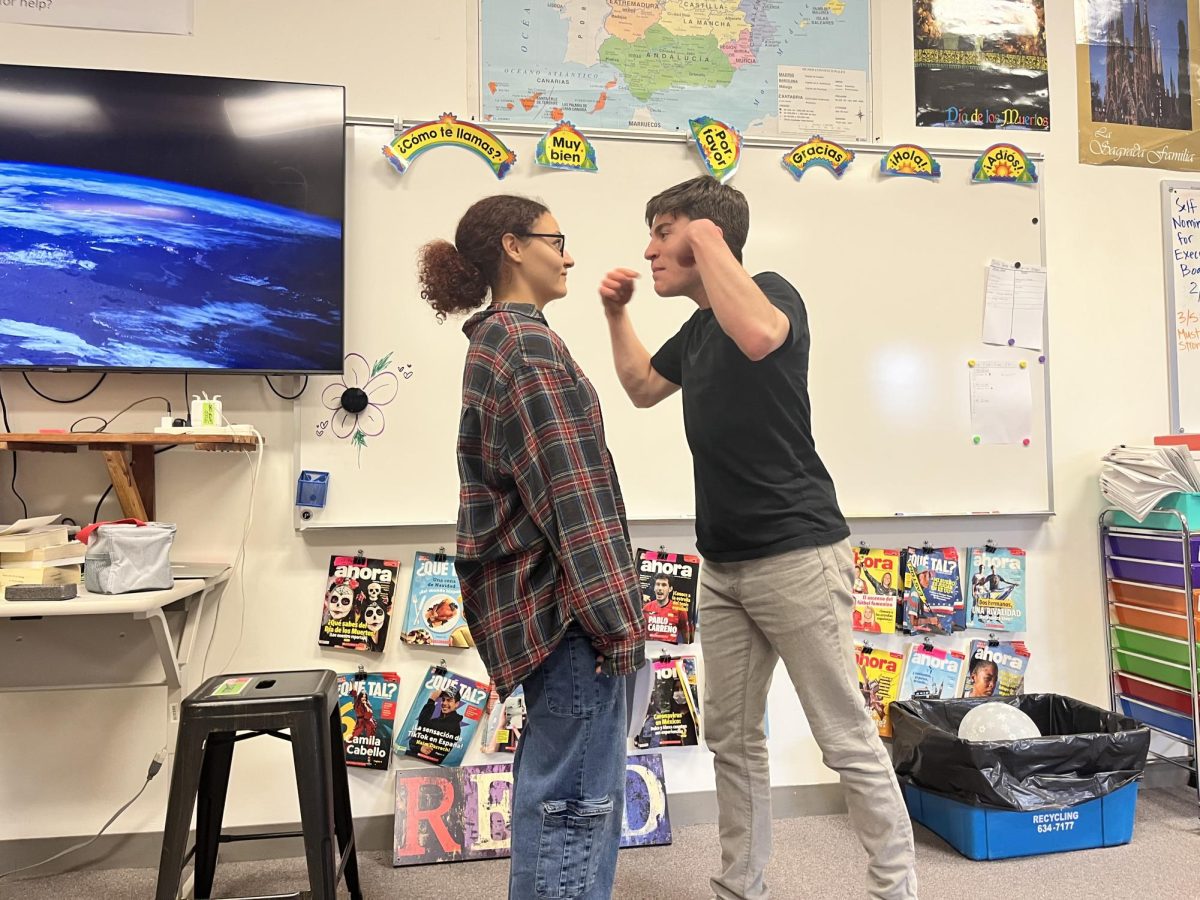

Musicians had to adapt to playing in a social distanced environment by using custom made masks, shields, and bell covers.

April 4, 2023

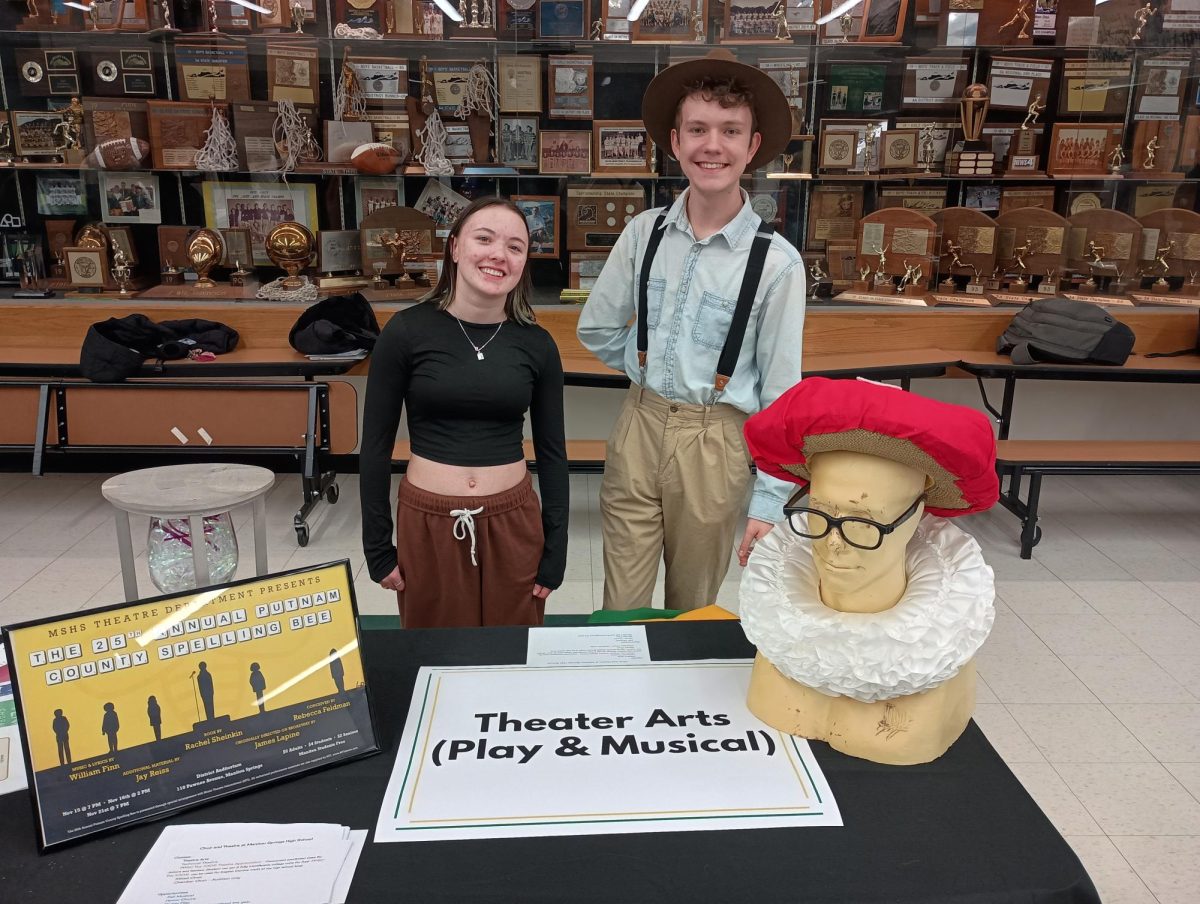

The trajectory of beginning band and orchestra students is a tale as old as time. Students try their hand at an instrument, most likely making some sound akin to a barn animal and the choice suddenly becomes clear. Families sink money into rentals, reeds, mouthpieces, cleaning kits, lessons, music stands and method books. The student joins their school’s beginning band or orchestra, setting off on an entertaining journey of soulful friendships and music. Not only are these first few years chock-full of memories, but they are crucial in learning the fundamentals of musical education; fundamentals that students are now scrambling to catch up to in the aftermath of COVID-19.

It had been my fourth year involved in music when quarantine was officially mandated in March 2020. I had played oboe for Philharmonia at the time, a full orchestra ensemble with the South Dakota Symphony Youth Orchestra, and I witnessed the snowball of events that led the world to shut down in an effort to combat the virus, and by association, the cancellation of the entire concert season.

After an attempt at Zoom rehearsals, which went as well as could be expected given the circumstances, I eventually returned to playing the oboe in a group setting in late 2021, and unfortunately, it was never the same. What had once been a tightly knit rehearsal, literally and figuratively as we shared laughter and squeezed into our chairs that were packed together like sardines, was now sterile. It was like operating inside a lab on an alien planet.

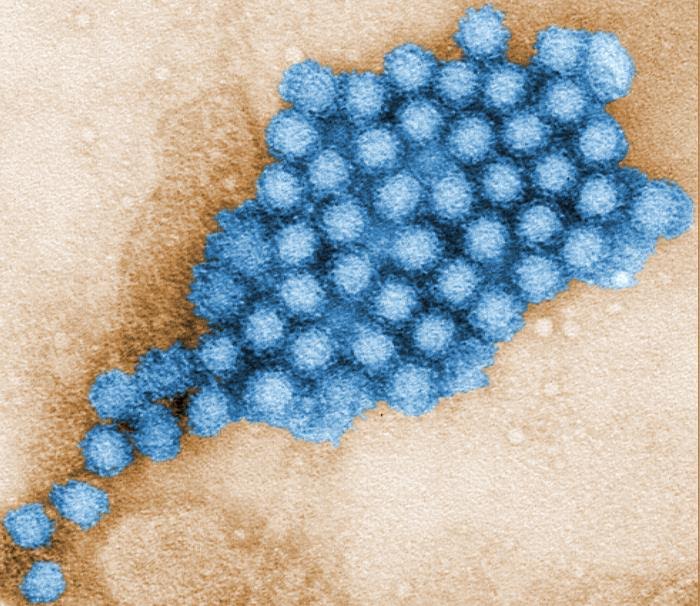

Each of us were social distanced across the room, some wearing masks with charming, incredibly inconvenient flaps for the mouthpieces, others with plastic shields strapped to their arms. Bell covers had been administered to each student, small to match the clarinet or gigantic to properly cover the tuba.

No one spoke, no one played above a mezzo forte. The sad truth of it was that we were lacking confidence. In multiple ways, we were lacking technical skill. As grateful as I am to have made music during a worldwide pandemic, to have found that connection among others, the experience had killed music for me.

A San Diego State University study measured the stressors music educators faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, finding that “given the kinesthetic nature of music, it was impossible during the lockdown to administer equivalent instruction and experiences within a virtual format. Participants noted high levels of concern for students pertaining to issues such as learning poor instrument habits and lacking interest or engagement.”

Music is inherently meant to be shared between people, and the pandemic reduced this ability to strictly virtual platforms. The word passion is so often thrown around the musical word, begging the question of if igniting a spark for the performing arts within students is even possible in an isolated environment.

Transilvania University’s study also explored the pandemic’s lingering effects on music education, particularly from the student perspective. “The lack of in-person interaction between teachers and students can generate different degrees of intolerance to uncertainty, which research has shown to directly influence the achievement of academic or professional performance,” the study stated. “In this regard, a number of studies have shown that anxiety is positively associated with performance.”

Not only are music students somewhat stunted in their ensembles by the lack of fundamentals, but performances are met with heightened levels of uncertainty and anxiety. No skill will ever improve without practice, and dedicated musicians are clambering to make up for their losses, while others simply do not have the desire to try because they are not invested.

I have absolutely carried over this sentiment of anxiety and low confidence within performance since the pandemic. Yet as opportunities have risen, I have been able to take part in higher ensembles such as the Colorado Springs Youth Symphony Association, as well as honor groups such as the Alamosa Top of the Nation Honor Band.

Playing oboe for these groups has been an illuminating experience; my peers are diligent and excited, wholly focused on the task at hand, and in turn so am I. There is an obvious love and care for the pieces given to us, emphasizing how much music is still alive.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may have been bleak and isolated, but with a little dedication and passion, music will prevail.