Madison Cavender digs deep into her roots

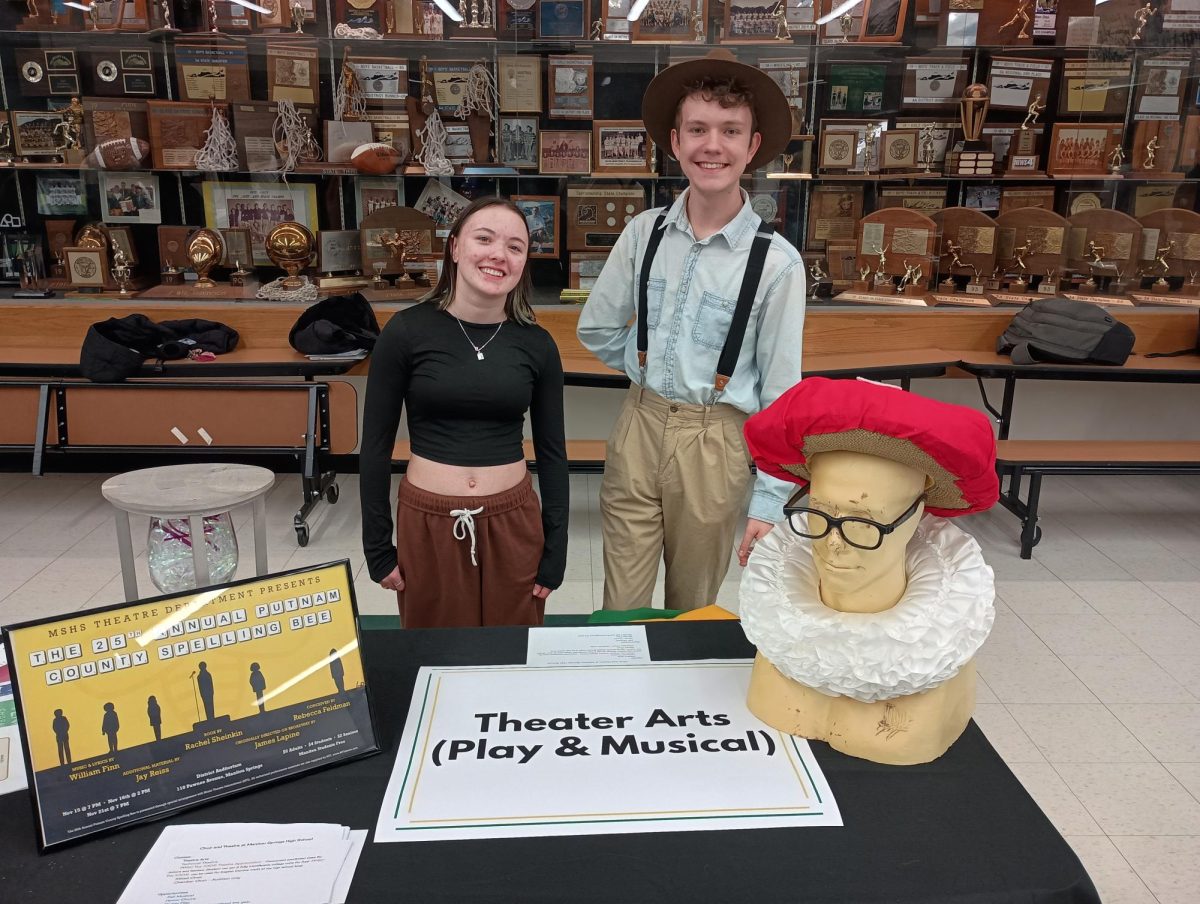

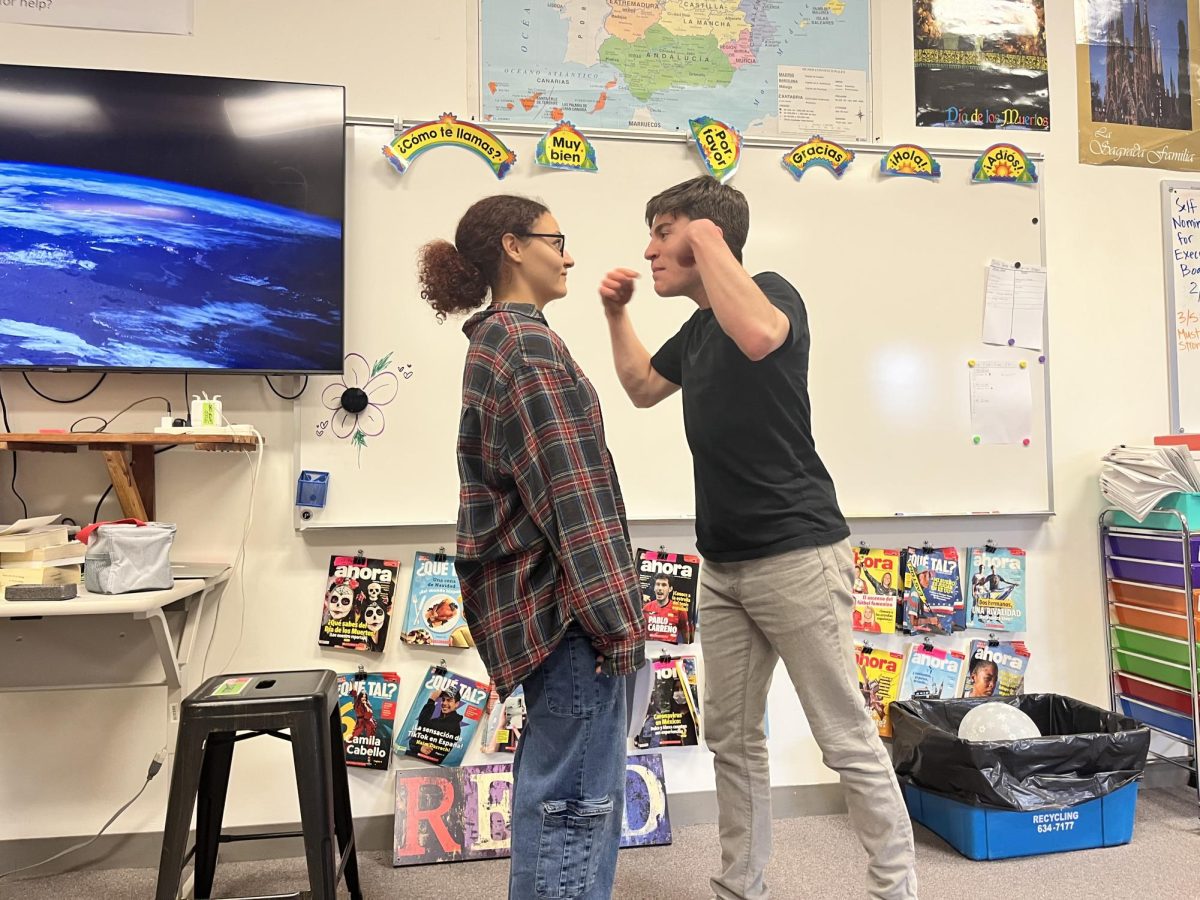

Madison Cavender dresses in her traditional regalia. She gave a presentation to Trevor Robbins US History classes last year.

December 12, 2022

Revitalizing a dead language is not typically a staple of childhood, but for Madison Cavender (12), it is one of the many pieces comprising her rich cultural identity. From powwows to entertaining winter stories to royalty, Cavender has experienced it all.

Cavender’s family history within the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, pronounced my-am-uh, traces deeply through her mother’s side of the family.

“We were forcibly removed from the land we were given in Kansas to where we are now in Oklahoma,” Cavender said. “My tribe originated up in the Great Lakes region. Ohio, Indiana and some parts of Canada, like Quebec, is where our tribe originated from.”

Forced removals by the U.S. Government and Native American boarding schools with the intention of eliminating all Native culture have unfortunately led to the deconstruction of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and many other tribes.

Cavender has been working towards revitalizing her Miami culture and the Myaamiaataweenki language, pronounced mya-mya-te-wengay, both at home and out in her community.

“It’s something that is different about me than everyone else,” Cavender said. “Most kids can’t say I grew up going to powwows. I grew up learning another language that died.”

Easy access to common words and phrases of the Myaamiaataweenki language can be found in the Reminder’s App on Cavender’s phone, as well on the sticky notes placed all over her house serving as reminders of what certain items are.

No one is yet fluent in Myaamiaataweenki, a fact of history that Cavender and the other members of her tribe have been working passionately and diligently to change for about 20 years.

Cavender’s family visits Oklahoma every June to partake in the events of their tribe. Language camps are a vital part of Cavender’s experience, practicing immersion by only speaking Myaamiaataweenki for a certain amount of time without any English.

“We started out with five minutes and got up to half an hour with each of us leading at times,” Cavender said.

Cavender finds even more success speaking the language at home with her family. “There have been times that I have done it on my own with my family, and I have lasted over an hour speaking just the language,” Cavender said. “I can have entire conversations with my mom in the language which is incredibly cool.”

Cavender’s summer spent with her tribe consists of many festivities, including powwows, delicious food, with fried bread being a personal standout for Cavender, and an assortment of games and dancing.

Delaney Bartko (12) has come along with Cavender to these events twice before, having the exciting experience of dancing alongside Cavender and her family.

“They have these huge drums that they beat on and the wardrobe is incredible,” Bartko said. “My favorite part was the outfits, because they had a lot of really cool outfits with really bright colors.”

As she was a visitor, Bartko wore a visitor shawl with bouncing tassels lining the bottom during the dance. Bartko was impressed by the beadwork and regalias, all handmade by members of the Miami Tribe.

“Everyone pretty much knows everyone, it’s one big community,” Bartko said.

Alongside the powwow, the Stomp Dance is always a highlight for Cavender, as well as for her sister, Katie Cavender (8).

“I most look forward to dancing and learning more about my culture,” Katie Cavender said. “My two favorite dances are the Shawl Dance at the powwow and the Stomp Dance at the bonfire.”

The Stomp Dance is a traditional dance performed in an alternating pattern of men and women. Women are shell shakers, having condensed milk cans tied around their legs, and men are callers, meaning they sing.

“Stomp is so much fun and it’s a lot of fun to listen to,” Madison Cavender said. “It sounds beautiful.”

Cavender also had the honor of being elected Junior Princess during her freshman year. As Junior Princess, Cavender had the responsibility of being an ambassador for her tribe and reaching out to her community.

“I do this either way, regardless,” Cavender said. “I’ll go talk to classrooms. I’ll talk in the community here in Colorado.”

Cavender’s role is rapidly growing given that she will be a voting member of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma next year.

“Next summer when I go out, I’ll be able to vote on these important things before I’ll be able to vote in our U.S. election,” Cavender said.

The revitalization of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma has come a long way, now having their own Cultural Center and amassing enough turnout for a gigantic Annual Meeting. Cavender is currently one of over 5,000 members in her tribe.

“When my mom was a kid and my great grandma would go to meetings, they had 50 members and they would end up with a potluck at the post office,” Cavender said.

The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma as it is today is only possible through the commitment and care from Cavender and the others of her tribe. Cavender’s generation especially has been paramount in revitalizing Myaamiaataweenki.

“Seeing how my generation has been able to bring this back, it’s pretty incredible,” Cavender said.